PSA: Site under construction! Links may not work yet

HYPEROBJECTS IN MEDIA: FROM LOVECRAFT TO LOCAL58

An essay

...

Welcome to the age of hyperobjects.

Hyperobject is a term coined by environmental philosopher Timothy Morton, a word for things previously without name in English. Though it may not be immediately clear how, this concept can be extremely useful to developing your creative practice.The defining characteristics of these entities, then, may be hard to describe, since their very nature makes them difficult to see and conceptualize. Morton has suggested the following features as inherent aspects of hyper-objects:

They are Viscuous:

hyper-objects are sticky. They attach to things and don't let go; they are inescapable. You're encapsulated within at least several at this very moment. Global warming, the internet, and numerous manmade substances like plastics. Is it possible to detach yourself from any of these? Not entirely. Even if you moved to a remote island with no internet access and and never saw a plastic bottle, your environment would still be affected by the production of these things. There would still be satellites flying overhead, the weather would still be changing, affecting your food and water, and plastic would continue to be dumped into the ocean, where it is consumed by fish, who you go on to eat, consuming the plastic yourself. When the BPA in a plastic container binds to your hormone receptors and disrupts the function of your cells on a microscopic level, producing things like cancers, that cancer is a local, physical manifestation of the object of plastic; all the plastic in the world. Hyperobjects coat everything they touch, and the more you try to resist, the stickier they appear.They are Molten:

they are so massive as to distort human concepts of space and time, refuting, quote, "the idea that spacetime is fixed, concrete, and consistent" entirely. They exist in ways beyond our normal comprehension and scientific understanding of how things exist.They are Non-local:

This massive size means they cannot be perceived in any one complete form, location or time; they are not localized, they cannot be looked at directly. Climate change is the perfect example of this object: we have a concept of it, but can only feel it in pieces, when our own weather is strange, or when there's an unusually strong flood or tornado. Non-locality means that the object is so much larger and complete than its individual manifestations. When you make art, the people seeing it are seeing evidence of your existence, but cannot see your form just from looking at the marks you make on a surface. This is how the hyper-objects do.They are Phased:

hyper-objects exist in dimensions higher than what humans are physically capable of seeing. From our point of view, they are in constant flux, phasing through our own time and space. Timothy Morton explains it like this, quote: "If an apple were to invade a two-dimensional world, first the stick people would see some dots as the bottom of the apple touched their universe, then a rapid succession of shapes that would appear likem an expanding and contracting circular blob, diminishing to a tiny circle, possibly a point, and disappearing... A process is a real object, but one that occupies higher dimension than objects to which we are accustomed... A high enough dimensional being could see global warming itself as a static object. What horrifyingly complex tentacles would such an entity have, this high-dimensional object we call global warming?" If you took a toad, a car, or a human, and viewed them from the perspective of a higher-dimensional entity, you would see them through time as well; we would perhaps look less like what we see as ourselves, a solid body with roughly similar numbers of limbs, and more like a long, shifting noodle, our physical manifestation paired with our temporal lifespan. Humanity as a whole, alongside other species, would likely be seen as one large shifting tendrilous mass, growing and shrinking in segments of our massive body as environmental factors affect our population, like some kind of cosmic pasta bowl. Am I saying the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster is onto something? That's for you to decide.They are Interobjective:

That is, the relationships between objects. Global warming is again the easiest one to point at; it's formed from the interactions of dead animals which are now liquid fuels, manufactured objects like cars and trains, the giant gaseous elder being we call the sun, people who think NFTs are a good idea, and many other things. Hyperobjects have no single source. They are born from and live in the interactions of different objects and entities. Does this all seem kind of Lovecraftian? That's because it is.

So in the time since Lovecraft, what has come to define cosmic horror? There are no truly concrete rules, but several common denominators that concentrate the essence of the genre: fears of the unknown, of the unknowable, and of humanity's insignificance within the larger scope of the universe. Psychological breakdown, commonly resulting from, quote, 'the discovery of appalling truth' of their own insignificance and helplessness with which protagonists cannot cope. There are not usually happy endings in cosmic horror, as the fear within the genre lies not in ghosts, bones, curses or interpersonal relationships, but within total psychological breakdown, surrender, existential crisis, and a complete warping of human perceptions.

Why do hyperobjects matter?

So why is this concept important? It gives name to a threat so large we have no pre-existing words for it. Apocalyptic doesn't cover it, as not all hyperobjects cause damage to the earth. Regular old climate is a hyperobject when humans aren't destroying it. It's just that now that the object is damaged, once we've noticed it, we cannot unsee the blood in the water. The concept of hyperobjects can help us work past:

⦁ restrictions of the human brain when conceptualizing large systems

⦁ the limits of language

⦁ visualizing time, and multiple dimensions

Appearances in media

Aside from Lovecraft, hyperobjects appear in tons of media of all varieties. In both novel and film versions you have Jeff VanderMeer's Annihilation, in comics you have the work of Junji Ito, especially Uzumaki and Remina, as well as Charles Burns' Black Hole. The word hyper-object itself takes inspiration from the music of Bjork, who since the invention of the word has become a friend of Morton's and engaged with their philosophy directly. The Twilight Zone is an extremely varied show in both its radio and television incarnations, but many of its storylines lie heavily within the hyperobject framework. Hiyao Miyazaki also engages with them in his works. Miyazaki has always had an extremely ecological mindset, and his visions of interactions with incomprehensible environments and beings- the toxic jungle of Nausicaa, the massive, viscuous forest gods of Princess Mononoke- show rich narratives of the ways humanity coexists with beings we can never fully understand. Most recently we've seen the development of A R G projects, unfiction, and especially a genre-within-a-genre: analog horror. These projects are typically nonlinear, video-based, and produced by individuals or very small teams. So far they have several defining influence and features: found footage elements, pre-digital technologies, cosmic threats and beings, glitched and warped footage and characters, and progressions either to apocalypse or radical transformation. A series called Local 58 is usually considered the trope codifier for this genre. If you watch any amount of it you will quickly grasp what analog horror is all about- the subgenre has been getting a lot of attention recently, so there's no shortage of projects to explore further. If you're interested, some of the other popular series include The Mandela Catalogue, Gemini Home Entertainment, and The Walten Files.

So how is the concept of hyperobjects useful to creative practice? Morton has said that "we need philosophy and art to help guide us, while the way we think about things gets upgraded" so that we can be mentally equipped to deal with the new era of life among these entities. The fact that their visible emergence via the work of Lovecraft birthed an entire genre is telling, but what about people who don't work in cosmic horror? While they may be more directly relevant to your work if you fall within the horror and climate fiction genres, they may also be a particularly useful concept if you work within cyberpunk, solarpunk, alternate history, magical realism, romanticism, and gothic, especially regional subgenres like Southern Gothic.

Lovecraft's fiction shows the psychological breakdown that can result simply from trying to perceive these things at full scale, but in the 21st century, we have no choice. If we want to have healthy, longlasting environments and societies, we have to look into the maw of the beast. We have to perceive the Old Gods. We're already aware of their presence, so ignoring them does nothing but create anxiety. So how do you write about things so large and powerful that comprehending them can drive you to madness, but in a way that invites you to do so? How do we look at Lovecraft's monsters and remain sane? Should this even be the goal? The old ways of identifying the beast, then killing it with mobs and pitchforks (problem solved!) don't work anymore.

Much research is now being done on climate fiction, and how to make appealing stories that help humans understand the mess they're in without causing a Lovecraftian psychological break. In my studies of this research I have identified many approaches to writing about the hyperobject of climate, and a handful of specific practices that may assist in helping audiences engage with this kind of fiction. I believe they likely work for other hyperobjects as well. If you want to create a dystopian alternate history detective story about the internet, set in 1990's Europe, these concepts probably apply. If you want to create solarpunk Afrofuturism, they probably apply here too.

First of all, know your audience:

If possible, it's useful to envision who you're making a project for. Different people care about different things; this can help you tailor your work to what most effects them. Knowing your intended reader's culture and mindset can help you engage them more effectively through description of objects, places, actions and emotions that matter to them.Related- make it relevant:

People tend to be more intrigued by the effect of things on their personal lives than on the facts themselves; knowing how to make situations relevant to your audience in different ways: cultural, political, social, regional, etc... can be a very useful tool. Here's an example: say you're writing about a family in the Deep South, where Hoppin' John is a dish made from rice, onions, peas/beans and a meat (usually pork), frequently eaten for New Year's to bring the community together and herald good fortune in. It's one thing to tell your readers there's a new, aggressive blight affecting crops. It's another to show plates half empty of a traditional dish on a special holiday because 90% of the peas sickened and died.Have resilient, relatable characters:

as previously noted, hyperobjects are terrifying. In studies of climate fiction readers most of the responses to 'how did this book make you feel?' were overwhelmingly negative- the positive ones, though, mostly came from readers being able to identify with and care about characters who displayed resilience in the face of hyperobject-induced adversity (Schneider-Mayerson 2018). It's good to be able to remember there's hope, resourcefulness and adaptation in all of us.Address things of value:

A 2021 paper from the University of Leeds (Harcourt et al, 2021) identified core things that made a pleasant life to people engaged in a climate fiction writing workshop- "family, friends and community, being able to make a livelihood and having some enjoyable leisure time, good-quality, locally grown food and greener environments." While this study was restricted to residents in the North of England, the values of family, health, livelihood and leisure generally extend across all cultures; these are things to address in your work if possible, as they are broadly relatable things that almost everyone cares about and desires. You might not only show how they are affected by whatever hyperobject you work with in a negative way, but also how they persist and adapt, while acknowledging the contribution of the past.Show the passage of time:

Humans don't live long enough to perceive hyperobjects at scale; setting stories in the future, over multiple generations, or across any significant expanse of time from our own, enables us to visualize the before-and-after of our present state and what effect we and the hyperobjects have on each other. When discussing climate fiction this is sometimes called the 'slow violence'; we often cannot perceive our actions (ie dumping in the oceans, which we all contribute to despite not throwing the trash in directly) until we see drastic consequences. (species extinctions and an impact on our oceanic food supply due to plastic pollution). The fancy phrase for this is 'reconfigure temporal perception' and according to studies it may help us comprehend "gradual socioecological changes that occur too slowly for human perception" (Schneider-Mayerson 2018)Also, have moments of vivid imagery:

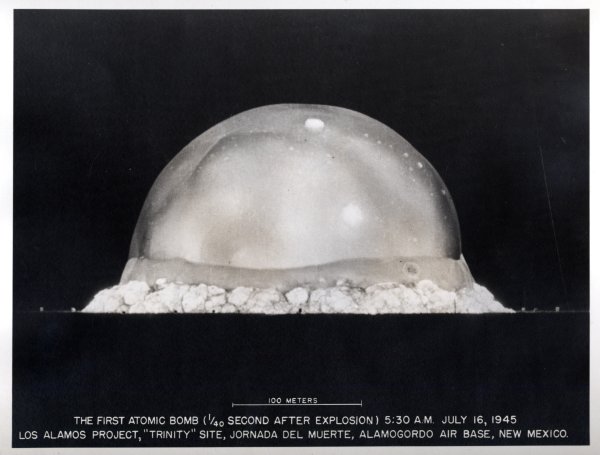

Studies have shown that bold, impactful images and scenes lead to more narrative engagement and recall later on (Schneider-Mayerson 2018); take a moment and think of a moment in a book, movie or game that still sticks with you today. What made it so impactful? How would you go about recreating that emotion in your own work?And keep in mind- grimdark may be counterproductive:

"the psychological tendency to avoid stories that deliver negative emotions means that well-intentioned authors who vividly depict the catastrophic consequences of climate change may actually be hindering their goal of heightening environmental consciousness." (Schneider-Mayerson 2018) This isn't to say tread so softly as to avoid upsetting anyone; it's to say don't overwhelm the audience entirely with doom and gloom. This is a problem now being studied with relation to how news media, especially, discusses climate- environmental psychologist Dr Robert Gifford, of the University of Victoria, has modeled a system of reasons people fail to adopt pro-climate behaviors called the Dragons of Inaction. He points out that "emotion, including fear, plays an important role in denial" (Gifford, 2011) therefore it may be important to stay mindful of just how much you can frighten your readers without shutting them down, as overall less people will want to engage with work that they find deeply upsetting in the first place... and those who do are still more likely to be put off by it.Lastly, consider the role of setting:

There is debate around the usefulness of regionally-specific eco-fiction, but alongside character identification, place was also mentioned frequently as invoking empathetic responses in readers. Gifford acknowledges in his Dragons of Inaction research that the role of place attachment in environmental behaviors is likely complex, but it is mostly accepted that people are more likely to care for a place they care for and feel attached to. To show the impact of your hyperobject, be it climate change (flood damage to historic homes), internet (this could be anything from fiberoptic cable being dug under a local landmark to pointing out the 'physical' changes to a VR space in response to events), contagions (well-loved public spaces falling into disrepair, etc) consider utilizing your setting to the fullest.Much of this can be taken as general writing advice regardless of whether you're dealing with hyperobjects or not, which is perfectly fine. Advice may be too strong of a word, since research is always changing, and these are more just things to think about and ask yourself when planning a project. Though they are taken from climate fiction research specifically, I would put again forth the idea that the same principles apply regardless of the hyperobject; the psychological impact of media dealing with other hyperobjects is scant, but climate is extremely well-studied. If you feel any of what has been stated here can be applied to your creative projects, regardless of medium or genre, then spend some time figuring out what kind of effect you want to have on the consumers of your work. And be creative in applying these principles! See how you can take the example situations I've used and apply them to anything- try romanticism and drama. This may look something like Lars von Triers' Melancholia, a 2011 art film exploring the nature of depression in the face of a wedding and an incoming planetary collision. A more scifi-action example might be Shane Acker and Tim Burton's 9, an animated film about ragdoll-like creatures in a damaged post-human world trying to solve the mystery of their own creation. Hyperobjects appear everywhere and are deceptive by their nature; there are a million ways to apply the concept beyond what may be obvious. Lovecraft gave them form, and Morton named them- the task set to us as creators of the 21st century is to go beyond the horror of perceiving them as monsters, and imagine new worlds where we might live with them; because we already do.

...

Sources:

Morton, T., 2013. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. 1st ed. University of Minnesota Press.

Harcourt, R., Bruine de Bruin, W., Dessai, S. and Taylor, A., 2021. Envisioning Climate Change Adaptation Futures Using Storytelling Workshops. Sustainability, 13(12), p.6630. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/12/6630/htm

Schneider-Mayerson, M., 2018. The Influence of Climate Fiction. Environmental Humanities, 10(2), pp.473-500. Available at: https://read.dukeupress.edu/environmental-humanities/article/10/2/473/136689/The-Influence-of-Climate-FictionAn-Empirical

Gifford, R., 2011. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers that limit climate change mitigation and adaptation. American Psychologist, 66(4), pp.290-302. Available at: web.uvic.ca/~esplab/sites/default/files/2011%20Climate%20Change%20in%20AP%20Dragons%20.pdf

...

Further reading links: